We live in a time full of action. Everywhere, we are expected to respond, to express, to decide; yet it is rarely asked what sustains action when its direction is no longer given. Where does genuine action begin, if not in outcome? What kind of action can still bear truth when certainty is gone? These were the questions that led me, unexpectedly, to a forgotten philosopher: Rudolf Eucken.

A philosopher teaching in Jena, Eucken wrote at the turn of the twentieth century about activism as a philosophy of life. For him, activism was not the same as political protest, nor was it reducible to social reform as it is understood today. It named the idea that a life of the spirit must be realised through action. He held that “life must be raised to an essentially higher level,” and that this elevation “cannot be a mere process occurring in man, but must be his own act and deliberate choice.” [1] Though his work emerged in Germany, it found resonance far beyond Europe, especially in parts of East Asia where similar questions of spiritual renewal and modern life were being asked.

Philosophical background

In the history of philosophy, action has often been treated with suspicion. The highest truth, it was said, required detachment, a contemplative distance from the disorder of the world. Plotinus, an influential Platonist philosopher, gave this idea its sharpest expression: “everywhere we will find that production and action are a weakened form of contemplation or a consequence of contemplation; a weakness where a person has nothing in mind beyond what has been made, a consequence where he has something prior to this to contemplate which is superior to what has been produced.” [2]

Action was increasingly marginalised in late nineteenth‑century thought. As naturalism rose to prominence, fuelled by Darwin’s biology and thinkers like Haeckel, it began to treat human action as merely the result of instinct, environment, and evolutionary drives. This led to a growing belief that actions are merely by‑products of mechanical or hereditary processes, not genuine expressions of soul, reason, or moral agency. Haeckel even claimed that “this hypothetical ‘spirit world,’ which is supposed to be entirely independent of the material universe, and on the assumption of which the whole artificial structure of the dualistic system is based, is purely a product of poetic imagination […] The dogma of ‘free will,’ another essential element of the dualistic psychology, is similarly irreconcilable with the universal law of substance.” [3] This worldview turned spiritual effort into a quaint relic of a vanished age.

These dominant views in philosophy and science left little space for a view of action as essential to human beings. Detached contemplation, on one side, and biological necessity, on the other, both displaced the possibility that action might disclose or constitute truth. Eucken regarded this not merely as a philosophical mistake but as a spiritual loss. For example, naturalism, he said in his Nobel Prize lecture in 1909, reduces human life to a norm in which “action is never directed toward an inner purpose but toward the utilitarian purpose of preserving life.” [4]

It was in this climate that Eucken developed his philosophy of Activism. He rejected the longstanding division between contemplation and action, insisting instead that true spiritual life requires their integration as aspects of the same movement toward a higher reality. “The basis of true life,” he wrote, “must continually be won anew.” [5] Such a basis is neither given in nature nor found through contemplation alone. It must be realised in life through human effort.

Before we consider what activism means for Eucken, we must examine the conditions that make it necessary. The first is the fractured state of the world around us; the second, the inner division within the self. Eucken refers to these as the outer and inner worlds, or the conditions that call spiritual action into being. [6]

The outer world

More than a century has passed since Eucken’s writing, yet the world he described – fractured, fast, and inwardly disoriented – could just as well be ours.

The problem begins with the collapse of the metaphysical and ethical frameworks that once gave human life orientation. To Eucken, this is not a passing crisis but a deeper historical shift in which “the basal nature of truth itself” has been thrown into doubt. People no longer believe in what once ordered the world. Yet the abandonment of former systems has not provided new foundations. One’s sense of purpose falters because one no longer knows what is real, what has worth, or what commands his commitment.

The vacuum left by these collapsed systems has not remained unoccupied. In their place, competing frameworks have rushed in: some grounded in God, others in nature, society, or personal will, but none form a coherent whole. Their coexistence is not reconciliation but contradiction. Each claims to account for life as a whole, yet each invalidates the others. With no inner principle to unify them, the individual is pulled in opposing directions, unable to commit with coherence or act with conviction.

This crisis is reinforced by the dominance of object-centred systems in science, industry, and public life, which has led to the disappearance of “all inner community of life.” They begin with what can be measured; their strength lies in control and utility. Eucken notes they “begin too quickly with objects,” pursuing results over understanding. He describes a division of labour between subject and object that has deepened into alienation. As objectivity hardens, subjectivity weakens.

Moreover, the pace and variety of modern life create a constant stream of impressions that overwhelm rather than guide. In such a world, the self cannot pause, reflect, or bind experience into any lasting form. It might attract or entertain us if it were merely a drama, Eucken says, but it is not. Distraction replaces depth, and the inner life, instead of directing the course of experience, is scattered across it.

The inner world

For Eucken, the spiritual centre of life is not fully given; it must be awakened and sustained through inner effort. Where this effort is absent, the inner world remains undeveloped and vulnerable to disintegration.

This vulnerability deepens as the inner life absorbs the confusion of the outer world’s surroundings. The collapse of shared frameworks has not freed the soul, but turned it into a battleground of opposing demands. The individual speaks in many voices, drawn to various goals, unable to unify life into a single direction.

Modern culture offers the individual great freedom, yet this freedom lacks direction. The power to choose remains, but the sense of what is worth choosing has faded. The individual conceals their uncertainty through constant activity, appearing restless and open to many possibilities, yet lacking an inner centre. What appears as freedom turns out to be a form of inward instability. In response to this, modern individuals try to form a worldview by stitching together partial systems. A little of religion, a little of nature, a little of art or reason or society. But these fragments do not form a living whole.

Such attempts often end in retreat into dogma or the repetition of dead forms. They return human beings, by a detour, to the very emptiness they sought to escape. Eucken warns that these strategies fail because they do not arise from the necessities of present life. Eucken argues that the inner world must find a new form. And this necessity demands a new philosophy.

As a summary, here is a concrete diagnosis of Eucken of the above problems: “the great world appears to us to be a meaningless machine; and in the struggle for existence the earlier harmony is forgotten. We perceive in man far too much that is insignificant and far too much selfishness, emptiness, and mere show for us to be able to regard him as being inwardly complete. Lastly, the modern strengthening of the subject and the ceaseless growth of reflection have so fundamentally overthrown the immediate relation of man to the world that only a far-reaching transformation of life can prepare for a reunion. If our life is so full of problems and tasks; if we do not find ourselves in a completed world of reason; but if we must, with all our powers, work toward such a world, we shall turn to Activism as the only help possible.” [7]

The source of the act

Where modern activism begins with injustice in the world, Eucken’s begins with incompleteness in the self. He saw the crisis of modern life as threefold: the inner world is undeveloped; the outer world is distorted; and in trying to respond to both, people conform to patterns that offer relief from uncertainty.

For Eucken, the way out is not to add another system to the outer world. What breaks this state must be an inward demand from spirit, the pressure of a higher reality breaking into the everyday. But where does that spirit come from? He believed it is disclosed in experience, yet only if we turn toward it. When one acts not from interest, custom, or pressure, but from fidelity to something that demands more than one can fully grasp, one is already within the spiritual. Spirit is not an idea we could understand before acting. It is only implanted in us through action. That is why the philosophy of activism is not a doctrine, but a task. The highest spiritual world is not a place. It is a possibility that is only visible to those who begin to live as though it mattered.

Action, in Eucken’s term, is a life-process by which the self becomes real through ‘self-determining activity.’ It’s the deliberate turning away from appearance, from habit and mere immediacy, in search of a higher level of life. Through such activity, the individual gains spiritual independence, no longer ruled by impulse or external impressions, but oriented by an inner allegiance to truth. Each act that breaks from conformity and answers to the demand of spirit reshapes the self, giving it direction and depth.

To act in this way is to treat life not as a series of reactions, but as a question of form. For Eucken, activism is a metaphysical task: the demand that life be shaped by something higher than self-interest or conformity, and that this shaping must occur through concrete action.

Clarifying the spiritual life

Eucken’s philosophy of activism rests on a claim that many today find alien. He speaks of a ‘spiritual world’ and a ‘higher order of reality’ as if these were real dimensions toward which we might orient ourselves. But he gives no map. He does not define that world in rational terms, nor locate it in theology. And that’s the point, because if spirit could be reduced to definition, it would no longer be spirit.

Still, we can gain clarity by naming what spiritual life is not, and by addressing what it is often mistaken for.

First, inwardness alone is no guarantee of spiritual life. Eucken warns that passivity often hides behind the appearance of depth – an escape into sentiment or contemplation that avoids the ethical demand of action. He criticises those who seek unity with the All only in thought or feeling, while withdrawing from the concrete world. Real action must “grapple with things courageously” and engage the world’s resistance as the medium in which spirit takes form.

Second, action is different from mere outward deed. A person may be active all their life and never truly act in Eucken’s sense. To act is to place one’s life in service of truth by shaping one’s actual being. Such a person acts not for recognition or reward, but because their inner condition is attuned to truth. The act is not aimed at producing inner harmony; the harmony is its content, not its consequence.

Third, truth is not subjective preference nor social consensus, neither is it given as static doctrine. His key claim is that truth must be lived into, that it requires spiritual effort to become real in a person’s life. Truth exists, but we are estranged from it. Action is the means of reorientation, not because action creates truth, but because without action, the self cannot align with it.

Fourth, activism is not a method or strategy, but a metaphysical structure of human life. Here, activism is not about external change, though that may follow, but about a spiritual striving to bring one’s life into alignment with a higher order. Outward transformation, if it comes, must be the expression of an inward ascent.

Finally, though action begins inwardly, it is never merely personal. By “reaching back into the totality of the world,” each act binds the individual to a larger responsibility. People does not act in a vacuum, as Eucken wrote, “the spiritual movement manifests itself also in private life and in the relation of individual to individual. He who does not measure spiritual greatness by physical standards will often find more genuine greatness in the simplicity of these relations than in the famous deeds of history; and at the same time he will find that through these relations an effective presence of the spiritual life within human experience is strengthened.” [8]

To grasp the contours of activism, Eucken distinguishes it carefully from other philosophies:

- Pragmatism treats truth as a function of usefulness within lived experience. Eucken, while recognising the importance of action’s effects, reverses the evaluative priority: action must serve what he calls the spiritual order, not merely practical ends. The value of truth is not in its utility but in its alignment with a higher moral reality. [9]

- Aestheticism pursues unity and form, often elevating contemplative beauty as an ideal. Eucken acknowledges the value of aesthetic experience but warns that it can retreat from the tragic and conflicting demands of life. For him, beauty, when detached from ethical striving, becomes insufficient. [10]

- Romanticism values depth of feeling, openness to experience, and a return to inwardness. Eucken shares its concern for interior life but criticises its frequent lack of structural clarity. Without orientation toward spiritual discipline, feeling alone can become diffuse and uncommitted. [11]

- Intellectualism treats knowledge as the highest human pursuit, often separating thought from lived commitment. Eucken sees this as a loss of vitality and spiritual depth. For him, thought must be more than abstract reasoning; it must serve and arise from the movement of the spiritual life. Without this grounding, intellect becomes mechanical, bureaucratic, and estranged from genuine moral action. [12]

- Voluntarism regards the will as a primary, self-originating force. Eucken affirms the will’s centrality but argues that will alone, if unanchored in spiritual meaning, risks reinforcing the ego rather than overcoming it. For him, true action arises not from assertion but from inward transformation. [13]

Eucken’s philosophy is demanding, but it does not remain abstract. It insists that spiritual life must be lived, not theorised. The following examples are my attempts to show how Eucken’s idea of activism might take form in different lives in different circumstances.

Example #1. The teacher

Picture a high school literature teacher who has worked for years inside a system where the role of language has been decided in advance. Shaped by decades of authoritarian governance, the education system does not use literature to ask questions but to reinforce answers. Stories are selected for their loyalty to the state’s version of virtue; poetry is treated as decorative affirmation of acceptable feeling. Interpretation becomes repetition, not inquiry. Even ambiguity is scripted.

The teacher follows the syllabus closely, as required. At the same time, he treats the structure of a sentence, the shift in a line of dialogue, the silence at a chapter’s end, as events worth attention. He asks his students again what a passage gives and what it withholds, not to provoke doubt for its own sake, but to remind them that language does not always settle into certainty. Occasionally, when the syllabus allows for it, he brings in other texts as optional reading. Sometimes a student takes interest, and after class he gives time to speak further. These conversations extend the lesson into areas the curriculum does not forbid, but does not encourage either.

The teacher does not oppose the structure directly, but by working in the space that remains, he does not let it close around him. He often doubts whether his efforts respond to anything beyond himself. But Eucken did not locate spiritual life in success. He described it as a form of action that “involves the motive of aiding in the development of the world, of advancing everything good and true,” even when such effort appears fruitless. The life the teacher lives is not guided by institutional rules or personal ambition, but by a sense of what must be answered in the act of teaching itself. And that, for Eucken, is what makes it activism.

Yet Eucken’s demand cannot end with preservation. Spiritual life, for him, required the initiation of something that did not yet exist, a form in which truth could begin to appear. The teacher’s fidelity to language is serious. But Eucken would have asked: does it build anything beyond the line it draws? Does it give form to a standard that others can take up and continue? This demand does not require the teacher to transform the school or the system, but it may require that he ask what his teaching generates. The question is whether the classroom can also become a site of formation, where a different relation to truth begins to be lived and sustained beyond the isolated individual. Without such movement, the life of the spirit may remain private, but unable to extend beyond the self into a world that still needs form.

Example #2. The craftsman

Consider a craftsman whose name is known to no one beyond his town. He works alone, in a narrow workshop behind a plain house, repairing tools and making furniture. He is not a master in the public sense. His work does not circulate in galleries, nor attract those who speak of craft as lifestyle. The work comes slowly, and not always reliably, but he continues because it is the only kind of work through which he knows how to remain intact.

Newer materials cost less, last long enough, and keep their shape without care. He knows this, but there is something in him that does not permit him to do what he feels untrue to him. He has learned that each piece resists in a different way and that working it rightly is not to dominate it but to recognise its resistance. He bends when the grain will not permit a straight cut. He delays when the air is too wet for glue to hold. He will not seal joints with quick glue that cracks under strain, nor coat surfaces in polymers that hide the grain.

Eucken warned that when life becomes a process without inner participation, it becomes “a soulless mechanism.” The craftsman fears that condition. He fears that if he compromises even once, the inward alignment anchoring his work will begin to erode. He does not refuse the shortcuts for aesthetic reasons, or because he believes old methods are sacred. He refuses because, through disciplined attention and inward testing, he has come to recognise something that must not be falsified. He knows that the object must carry within it the trace of a real decision, not just how to cut or fasten, but why it matters that the form obeys the material.

The objects he makes are modest: a table that stands level or a chair that does not creak under weight. They may go unnoticed by others, but the act of making them did not go unnoticed in him. In that process, a higher order entered the world in a form that resists the logic of speed, profit, or simplification. And that, for Eucken, is the mark of action in the spiritual sense, the creation of a form that tells the truth, even when the world no longer asks for it.

The examples of the teacher and the craftsman show two contrasting orientations. One supports change, the other resists it. Both are engaged in activism as Eucken understood it, not because they provoke change or oppose it, but because each acts from a binding relation to truth. Sometimes truth will require change; sometimes it will require preserving forms that the world has stopped recognising. But in both cases, what matters is not what one breaks or preserves, but why.

Eucken in Western culture

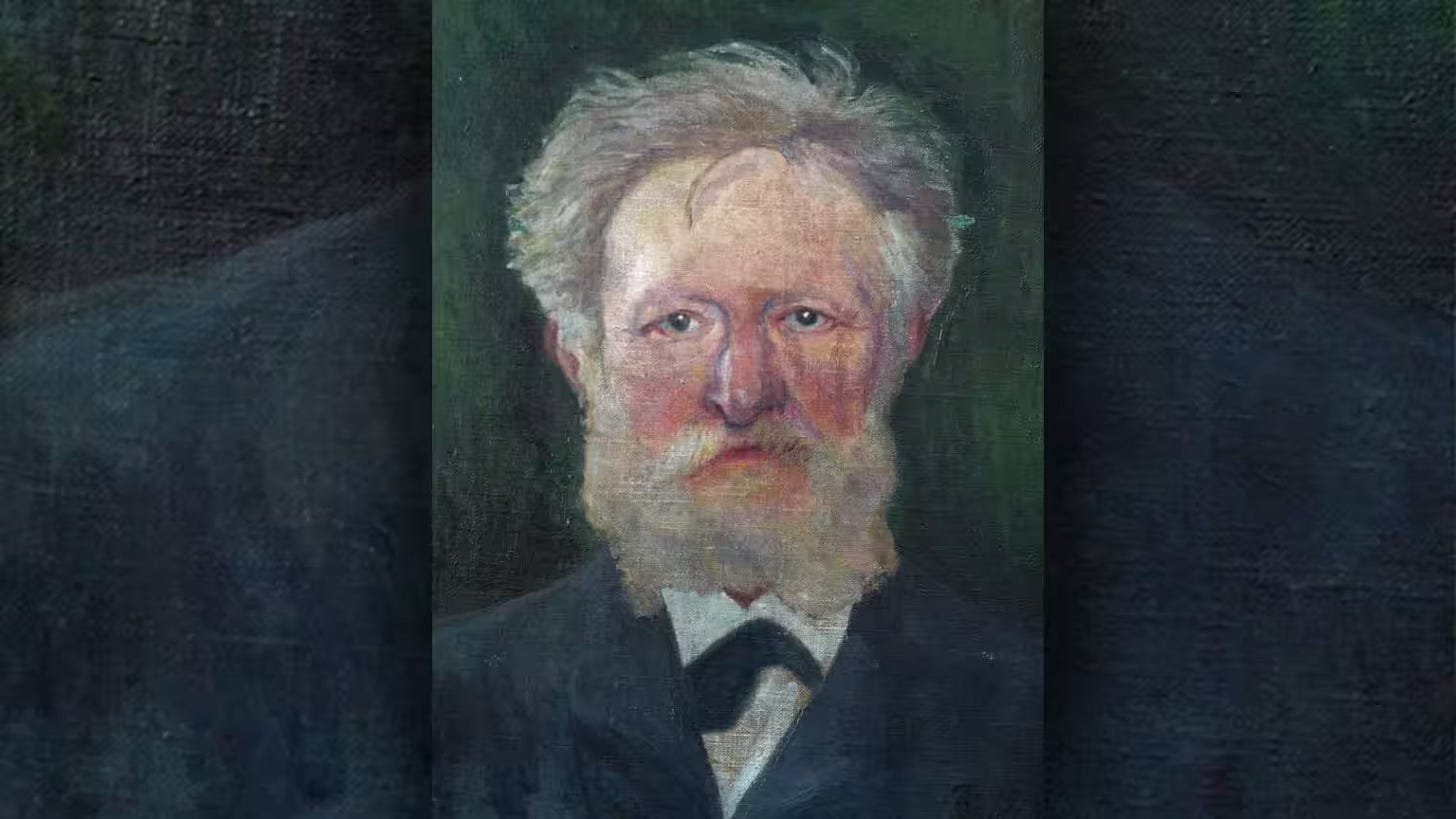

Eucken stood at the centre of German intellectual life around 1900. In 1908, he received the Nobel Prize in Literature for his “earnest search for truth,” a recognition of his philosophical commitment to the spiritual foundations of life.

Eucken’s emphasis on self-activity as a condition for genuine learning resonated beyond academic philosophy, touching cultural and educational movements. Charlotte Mason, an English educationalist, endorsed Eucken’s thought: “Activism is that every spiritual attainment, whether of mind, heart or soul, is the result of struggle, effort against opposition. This is the thought which underlies our method of requiring children to struggle with their books and know for themselves what they read, without the various explanatory devices usually employed by the teacher.” [14]

His philosophical influence continued through his students. Max Scheler, a central figure in phenomenology and ethics, earned his doctorate under Eucken, adopting some of Eucken’s concerns about the spiritual dimension of human existence. Eberhard Grisebach, another student, carried forward Eucken’s neo-idealism in cultural-philosophical form, even as he later diverged from him.

However, Eucken’s Activism did not develop into a lasting philosophical tradition. The failure is mostly because it stood at an awkward angle to both the philosophical and political movements that followed.

His commitment to spiritual life as a real task already set him apart from his contemporaries. As the century advanced, that distance grew. His version of activism requires the individual to stand, repeatedly, within conflict, without support from history or recognition. It offered no resolution, no stable identity, and no institutional reward. For that reason, it resisted becoming a school of thought. It asked not for agreement but for transformation, and that is difficult to teach.

Also, he wrote in the shadow of German idealism, but did not belong to it. He used its language but resisted its systematic metaphysics. At the same time, he was untouched by the emerging ideological frameworks that came to define the twentieth century. He was not a theologian, though spiritual life stood at the centre of his work. He was not a political philosopher, though his writing bore ethical consequences for public life. He tried to hold together metaphysics, ethical commitment, inner transformation, and practical action, without reducing one to the other. This made his thoughts difficult to categorise. Later thinkers like Hannah Arendt, Simone Weil, and Albert Camus addressed similar themes on philosophy of action but in more familiar genres: political theory, spiritual literature, philosophical fiction. Eucken’s fusion of metaphysical activism with spiritual ethics had no clear home.

Historically, the intellectual mood shifted. After the First World War, and more definitively after the Second, the idea of a supra-historical moral order lost credibility. Philosophy turned toward finitude, contingency, and historicity. In Germany, Heidegger redefined existential seriousness without Eucken’s appeal to spirit. In France, Sartre and Merleau-Ponty approached action and selfhood through phenomenology and social history. In the Anglo-American world, philosophy narrowed itself to analysis, language, and empirical precision. Within all these currents, Eucken’s notion of action as fidelity to a higher order came to seem both archaic and implausible.

Over time, the vocabulary of “spirit” and “truth” fell out of favour. As existentialism gave way to structuralism and critical theory, and analytic philosophy entrenched its scepticism of metaphysics, those who still spoke in ethical absolutes were treated with suspicion. It was not that Eucken lacked clarity, but the form of his seriousness became out of tune with a culture that prized critique and detachment. He refused to reduce human action to psychology, language, or power. That refusal made him difficult to absorb into traditions that demanded theoretical distance or empirical control.

Eucken’s influence in East Asia

In the early decades of the twentieth century, Eucken’s thought travelled beyond Europe and entered intellectual life in East Asia. This was not simply a matter of transplanting ideas, but of encounter: Eucken’s insistence on spiritual self-formation and ethical action intersected with longstanding Eastern concerns around moral cultivation, inner life, and the tension between tradition and modernity.

The idea that action is central to spiritual life is not unique to Eucken. Similar currents had long existed in East Asian philosophy. Wang Yangming’s teaching on ‘the unity of insight and action’ (zhi xing he yi / 知行合一 / tri hành hợp nhất) offers one parallel. [15] For Wang, genuine knowledge is inseparable from moral action; to “know” the good without acting on it is not truly to know at all. In this view, knowledge and action are not two faculties coordinated by discipline, but one movement of the moral mind.

However, Wang believed the world possessed a moral structure that could be trusted, that the mind, when properly cleared, reflects the whole of heaven and earth. Eucken stood in a more fractured landscape. For him, the spiritual order was not given in nature nor sustained by tradition; it had to be discovered and upheld through effort. Yet this very uncertainty is what made his thought more recognisable to East Asian thinkers confronting modernity. Beneath the differences of form lies a shared conviction: that human life must be shaped by inner responsibility, and that truth is not merely observed, but lived into.

In light of this tradition, it is not surprising that Rudolf Eucken’s philosophy found resonance in East Asia. His work began to circulate after he received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1908, and was soon translated, discussed, and engaged, particularly in Japan, where neo-Kantian and idealist influences were already taking root.

In the early 1910s, Japan experienced what came to be known as the ‘Eucken boom’ – a wave of interest in his work that reached beyond academic circles. [16] At the time, scholars and thinkers such as Nishida Kitarō were searching for ways to resist the excesses of industrial modernity without abandoning the modern project altogether. Japanese vitalism emerged as one such response; it “criticized European ‘material modernity’ and stressed to restore human spiritual values.” [17] It was within this intellectual climate that Eucken’s philosophy of activism found wide reception, read not only as European thought, but as a voice attuned to Japan’s own tensions between inner cultivation and outward transformation.

Through Japan, Eucken’s work entered Korea. Under Japanese colonial rule, Korean intellectuals were searching for moral orientation and cultural renewal amidst the erosion of traditional structures. Thinkers like Hyun Sang-yoon and Kwon Deok-gyu took Eucken seriously in this search. Kwon even likened him to Tolstoy, as a figure who offered spiritual and ethical clarity when both nationalism and imported ideologies seemed insufficient. [18] In a context where external forms of resistance were heavily suppressed, Eucken’s emphasis on inner transformation and moral self-activity resonated as a different kind of resistance. His philosophy entered a broader current in 1920s Korea that sought to respond to crisis through ethical reform rather than political doctrine.

In China, Eucken’s thought entered through a unique moment of philosophical self-examination. In the search for a renewal of ethical life, Liang Qichao placed Eucken alongside Bergson as one of the two most important philosophers of the modern world. Around 1920, he led a group of young Chinese intellectuals to visit Eucken in Jena, hoping to draw connections between Confucianism and a living European philosophy. [19] Eucken, for his part, saw in Confucian ethics a close affinity to his own metaphysical vision. In 1922, he co-authored a book titled The Problem of Life in China and in Europe with Zhang Junmai, where he expressed hope for “tight connection between East and West.” [20] In this context, Eucken also played an unexpected role in the history of Chinese metaphysics: it was through his work that the term became known widely.

Around the same time, Sun Yat-sen, exiled in Japan, was reading Eucken closely. A surviving book order list records that, over five months from November 1914 to March 1915, Sun purchased fourteen books from a Tokyo bookstore, and five of them by or about Eucken. [21] Sun appears to have drawn from Eucken’s work in shaping his metaphysical thought. Chen Lifu, then, read Sun’s remarks on life and spirit as authoritative and used them to justify his own adoption of vitalism to build Nationalist Party policy.

Looking back, what is striking is how Eucken’s work moved without a school or a formal system. His philosophy crossed borders through a shared concern that something essential had been lost in modern life. He arrived in East Asia as a reminder of something those cultures already knew, but perhaps needed to hear again.

Why this still matters

Long before modern debates on alienation or post-truth, Eucken recognised that the collapse of metaphysical orientation would leave people with freedom but no direction, choice but no criteria. He foresaw how theories and institutions could become superficial when not grounded in inward struggle. This critique is even more relevant now, in a culture that measures value by visibility, speed, and success.

That crisis has deepened. The more we attempt to correct or reform the world, the more entangled we become in its machinery. Each intervention deepens dependency. What we confront today is not merely disorder, but a kind of systemic entrapment.

In such a world, Eucken affirms the dignity of invisible work – acts whose effects may never be recognised, yet still bear spiritual weight. His idea of activism shows how one might act faithfully without institutional support, without resolution and recognition.

Eucken also offers a conception of spiritual life without dogma. He holds together ethical responsibility and metaphysical depth, and in doing so avoids both religious prescription and secular detachment. Most contemporary frameworks split these apart, either ethics without transcendence, or metaphysics without consequences. His thought shows that these two belong together, and that action must answer to both.

Eucken’s name may have faded from the centres of philosophy, but the questions he asked remain. What holds the self together when the world pulls it apart? What gives human action genuine meaning? And, most importantly, what prevents life from becoming a soulless mechanism? These questions stay with us as a philosophy of our own, one that unfolds only through experience, and whose answers take form in how a life is lived.

Notes

1. I’ve uploaded several works by Eucken to Google Drive; they can be accessed here: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1XMF8bgGeevJjzihOUSTkWTQa-uzB6rJy?usp=sharing

2. Rudolf Eucken is pronounced as Roo-dolf Oy-ken. In Japan and Korea, he is also referred to as Oiken.

3. Rudolf Eucken is the father of Walter Eucken, an economist best known for founding the Freiburg School and shaping the principles of ordoliberalism in post-war Germany.

4. While reading about Wang Yangming, I came across something interesting. I’ve lived in Taiwan for about ten months and have visited Yangmingshan, yet I never knew the national park was named after him. It was in 1950 that Chiang Kai-shek renamed the area in his honour.

5. In seeking answers to questions that are, ultimately, my own, I may have misunderstood or stretched the philosophers I’ve drawn on. But this risk is part of the willingness to think seriously and in good faith. If something here seems missing or wrongly taken, I welcome the chance to discuss. Please reach out: viyen.me@gmail.com.

References

Primary texts

[1] Eucken, Rudolf. The Life of the Spirit: An Introduction to Philosophy. Translated by F. L. Pogson. London: Williams & Norgate, 1909. https://archive.org/details/lifeofspiritint00euck/page/262/mode/2up (see pages xi and 262). [2] Plotinus. The Six Enneads. Edited by Lloyd P. Gerson. Translated by George Boys-Stones. Cambridge University Press, 2018. https://ia903408.us.archive.org/32/items/the-six-enneads/The%20Enneads%20Plotinus.pdf (see page 359). [3] Haeckel, Ernst. The Riddle of the Universe. Translated by Joseph McCabe. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1905. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/42968/42968-h/42968-h.htm (see page 90); alternate pagination available at https://archive.org/details/riddleoftheunive034957mbp/page/n87/mode/2up (pages 73–74). [4] Eucken, Rudolf. “Rudolf Eucken Nobel Lecture: The Meaning and Value of Life.” NobelPrize.org. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/1908/eucken/lecture/ [5] Eucken, Rudolf. Life’s Basis and Life’s Ideal: The Fundamentals of a New Philosophy of Life. Translated by Alban G. Widgery. London: Adam & Charles Black, 1912. https://dn790009.ca.archive.org/0/items/lifesbasislifesi00euckuoft/lifesbasislifesi00euckuoft.pdf (see page 255). [6] The two sections “The outer world” and “The inner world” in this essay are my own summary and interpretation of Rudolf Eucken’s philosophy, drawn primarily from “The Outer and the Inner World” in The Life of the Spirit (see [1]) and “Introductory Remarks and Considerations” in Life’s Basis and Life’s Ideal (see [5]). [7] Eucken, Life’s Basis and Life’s Ideal, 259. When Eucken speaks of the weakening of subjectivity, he is referring to the inner life – a centre of lived experience that possesses depth and the capacity to connect with the whole. In a modern world dominated by objectification, the subject in this sense becomes alienated, scattered, and loses its centre. Later, when he speaks of “the modern strengthening of the subject,” Eucken is referring to the modern self – the human being as an independent, analytical, and self-reflective subject. The stronger this subject becomes, the more it disrupts the direct relation to the world, because it no longer lives within a shared order of meaning but stands outside of it. [8] Eucken, Life’s Basis and Life’s Ideal, 269. [9] “Pragmatism and activism attach very different meanings to the union of truth with life. The former regards truth as merely the means towards a higher end (which seems to us subversive of inner life), while the latter makes it an essential and integral portion of life itself, and hence can never consent to it becoming a mere means.” Eucken, Rudolf. The Main Currents of Modern Thought: A Study of the Spiritual and Intellectual Movements of the Present Day. Translated by Meyrick Booth. London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1912. https://archive.org/details/maincurrentsofmo00euck/page/486/mode/2up (see page 80). [10] “Further, there must be no perplexities in our soul, and no deep conflicts within our being, so that this contemplation may occupy us completely, and be a source of happiness. Lastly, we must be closely and surely united with the world so that a change of life may be accomplished easily and smoothly. If one of these requirements is not satisfied; if, instead of this harmony, the world manifests severe conflicts and harsh contradictions; if such exist also within our soul; if, lastly, there appears to be a deep gulf between us and the whole, then the aesthetic solution of the problem of life is an impossibility.” Eucken, Life’s Basis and Life’s Ideal, 259. [11] “When such precedence is given to this Romantic tendency life threatens to become delicate, feeble, effeminate; it knows no energetic opposition to the flow of presentations; instead of a definite union it offers aphoristic thoughts and stimuli; through the lack of logical acuteness it falls into the direst contradictions; it sacrifices all distinct form and organisation to a revelling in vague moods. As in such a state of weakness the spiritual life does not succeed in gaining complete independence in face of the natural conditions of our existence, so it does not attain the necessary ascendancy over sense.” Eucken, Life’s Basis and Life’s Ideal, 260. [12] “However decisively, in consequence, we must reject the idea of making the intellect a scapegoat for everything we dislike in modern life, he who desires an independent and self-sufficing spiritual life and believes that if human life is to possess a true content it must be derived from this source, is thereby saved from any tendency to impart an intellectualistic form to life; he is much more likely to be extremely sensitive to the way in which the Modern World in particular (including our own age) has been swamped by intellectualistic movements.” Eucken, The Main Currents of Modern Thought, 82. [13] “In the life of to-day, voluntarism presents itself … as a scientific theory, which comes to the front, in the first place, in psychology as a movement which aims at demonstrating the dependence of the life of ideas upon the instincts and desires, and the conditioning of its entire course by a voluntary phase. […] it reveals itself in the prevailing view that the practical satisfaction of man (of man in relation to his immediate environment) is the one and only true goal – the pursuit of knowledge being looked upon as a mere means to this end and indeed a foolish waste of time unless devoted to the promotion of human well-being.” Eucken, The Main Currents of Modern Thought, 72-74. [14] Mason, Charlotte M. “Introducing Rudolf Eucken.” The Parents’ Review, 1914, pp. 312-315. https://charlottemasonpoetry.org/introducing-rudolf-eucken/ [15] Trần Trọng Kim. Wang Yangming. Saigon: Tan Viet Publishing House, 1960. http://triethoc.edu.vn/vi/chuyen-de-triet-hoc/triet-hoc-dong-phuong/hoc-thuyet-cua-vuong-duong-minh-5-tri-hanh-hop-nhat_1461.html [16] Choi, Ho-Young. Reception of R. Eucken’s ‘Neo-Idealism’ and the Development of ‘Culturalism’ in Korea and Japan. Japanese Criticism 17 (2016): 254-331. https://s-space.snu.ac.kr/bitstream/10371/135062/1/9.%20%EC%B5%9C%ED%98%B8%EC%98%81.pdf [17] Seo, Dong Ju. “Border-Crossing of Taisho Vitalism and Radical Theory of Individuality in Colonial Korea: On Genealogy from Henri Bergson, Ōsugi Sakae to Yeom Sang‑seop.” Buddhist-Christian Studies 18, no. 1 (2023): 133-151. https://www.bcjjl.org/upload/pdf/bcjjlls-18-1-133.pdf [18] See [16] above. [19] Nelson, Eric S. Chinese and Buddhist Philosophy in Early Twentieth-Century German Thought. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017. https://www.bloomsbury.com/uk/chinese-and-buddhist-philosophy-in-early-twentiethcentury-german-thought-9781350002555/. Available online at https://ebrary.net/94765/psychology/chinese_and_buddhist_philosophy_in_early_twentieth-century_german_thought [20] Peng, Hsiao-yen. Modern Chinese Counter-Enlightenment: Affect, Reason, and the Transcultural Lexicon. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2023. https://doi.org/10.5790/hongkong/9789888805693.001.0001. [21] Stumm, Daniel. “Revitalizing the Nation: Vitalist Philosophy in the Chinese Nationalist Party.” Parrhesia: A Journal of Critical Philosophy, no. 36 (2022): 201-221. https://parrhesiajournal.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Revitalizing-the-Nation-Vitalist-Philosophy-in-the-Chinese-Nationalist-Party_Daniel-Stumm.pdfAdditional Sources

Eucken, Rudolf. The Meaning and Value of Life. Translated by Lucy Judge Gibson. London: Adam & Charles Black, 1913. https://archive.org/details/themeaningandval00euckuoft/page/n11/mode/2up

Eucken, Rudolf. Rudolf Eucken: His Life, Work and Travels. Translated by Joseph McCabe. London: Adelphi Terrace, 1921. https://ia601509.us.archive.org/4/items/in.ernet.dli.2015.174834/2015.174834.Rudolf-Eucken-His-Life-Work-And-Travels_text.pdf

Jones, Tudor. An Interpretation of Rudolf Eucken’s Philosophy. London: Williams and Norgate, 1912. https://archive.org/download/interpretationof00jonerich/interpretationof00jonerich.pdf

“Eucken, Rudolf Christoph (1846–1926).” Encyclopedia.com. https://www.encyclopedia.com/humanities/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/eucken-rudolf-christoph-1846-1926

EBSCO Research Starters. “Rudolf Christoph Eucken.” https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/history/rudolf-christoph-eucken

Oxford English Dictionary. “Activism.” https://www.oed.com/dictionary/activism_n?tl=true